California’s Ebony Alert System Aims to Bring More Attention to Missing Black Girls and Women

Teen Vogue

Rita Omokha

February 8, 2024

In a landmark move to address racial disparities in missing persons cases, California passed the nation’s first Ebony Alert system. Effective last month, the emergency notification program, modeled after existing Amber and Silver Alerts, specifically focuses on missing Black children and young adults between the ages of 12 and 25.

The Ebony Alert initiative stemmed from concerns that Black missing persons receive less media coverage, public attention, and law enforcement resources compared to their white counterparts. Data from the FBI’s National Crime Information Center reveals that in 2022, Black children under 18 accounted for about 141,000 missing person cases, while Black women over 21 made up nearly 16,500. Despite these staggering statistics, Black missing persons are less likely to trigger Amber Alerts, which typically require evidence of abduction or imminent danger.

“In a nation where 39% of the missing are [minorities], and [Black people] only make up 13.6% of the [U.S.] population, the Ebony Alert is long overdue,” artist and producer Nicci Gilbert-Daniels tells Teen Vogue, referencing statistics from the Black and Missing Foundation. She says alarming statistics like this are why she founded From the Bottom Up, an organization dedicated to supporting Black women and girls, and why they advocate for missing women and girls. “We believe historical desensitization, negative stereotypes, and criminalization related to minority persons reported missing are problematic when trying to get justice and equity for our missing Black women and girls,” Gilbert-Daniels says.

Under the new system, law enforcement agencies will “request the Department of the California Highway Patrol to activate an ‘Ebony Alert,’ with respect to Black youth, including young women and girls,” the bill states, “who are reported missing under unexplained or suspicious circumstances, at risk, developmentally disabled, or cognitively impaired, or who have been abducted.”

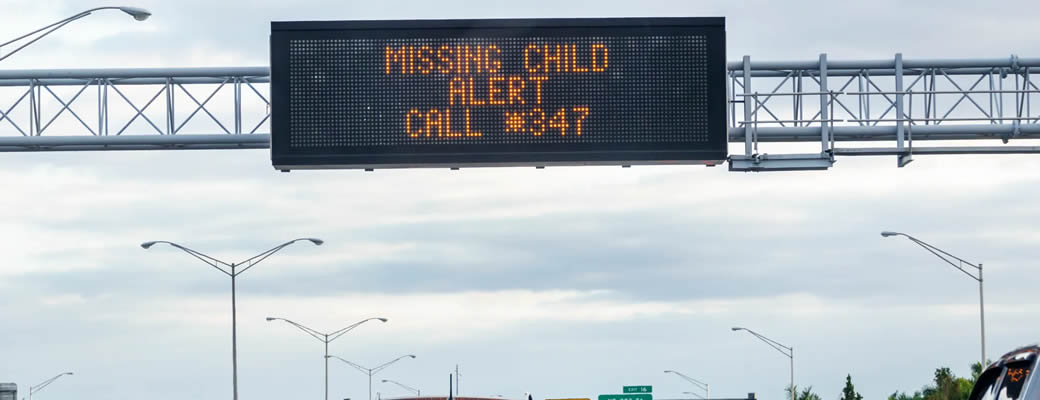

They’d utilize high-profile notification channels like electronic highway signs to display information about the missing person. They will also encourage media coverage from radio, television, and online news outlets.

Natalie Wilson, the co-founder of the nonprofit Black and Missing Foundation that tracks missing African Americans, tells Teen Vogue that, though the alert is a positive step forward, there are still many barriers — like stigma — to overcome. This is often prevalent in the phenomenon known as “missing white woman syndrome,” where media coverage overwhelmingly focuses on missing or murdered white women compared to women of other races or ethnicities. Take the case of Gabby Petito, whose disappearance garnered international attention compared to similar cases involving Black women, highlighting what many see as the racial bias inherent in some media reporting and the urgent need for equal attention to all missing persons.

“When we peel back the layers, we find that these [Black] families deal with several stereotypes that ultimately impact the resources and support they receive,” Wilson says. “Our missing deserves to be treated equally. Race shouldn’t be a barrier to media coverage and law enforcement support.”

Advocates say that’s particularly important when you consider the other vulnerabilities Black women and girls face. The Black and Missing Foundation found that even when Black children are missing, they are disparately classified as “runaways” in comparison to white children who are classified as “missing.” As a result, many Black children are relegated to being invisible when they go missing.

Terrion Williamson, PhD, professor of Black studies and gender and women’s studies at the University of Illinois Chicago, underscores that the need for a separate alert for Black people, in and of itself, “is indicative of a first-order problem,” one that she’s researched closely for years, and one her current project delves into, centering on nine Black women who were murdered in Peoria, Illinois, between 2003 and 2004.

“This speaks more broadly to how Black people are situated within the nation as well as to the specific issue at hand,” she says. “If, historically, the cases of missing and disappeared Black women and children and other marginalized populations had been given the same attention and visibility as prototypical, idealized missing person cases, which have tended to center normatively attractive, middle-class white women and girls who are deemed most worthy of care and, consequently, media and law enforcement attention, we might be having an altogether different conversation.”

While the Ebony Alert marks a significant step towards addressing racial disparities in missing persons investigations, its effectiveness will hinge on public awareness and collaboration. Or as Wilson put it: “We all play a critical role in helping us find us. It takes all of us – media, law enforcement, community, and elected leaders to help protect, amplify and find those missing from our communities.”

Despite concerns about its limitations and execution, Ebony Alerts could potentially revolutionize the way missing Black persons’ cases are handled across the country. Ultimately, its launch in California serves as a reminder that the fight for racial justice should extend to every facet of society, including creating a more equitable and responsive system for all missing persons.

“We must understand the Ebony Alert as a first step and not a final goal,” Dr. Williamson says. “The disproportionate rates of Black children and Black women among the missing — many of whom are older than the Ebony Alert’s 25-year-old age cutoff — is not simply a matter of when and how alert notifications are made but is the outcome of a confluence of harms that must be addressed in their entirety if the concern is truly about making Black children, women, and communities safer.”

Photo credit: Jeff Greenberg/Getty Images/Teen Vogue