The Shocking Reason You’ve Probably Never Heard About These 265,000 Missing Americans

TakePart

Britni Danielle

July 25, 2014

When Natalie Holloway went missing in 2005, most Americans couldn’t turn on the television without hearing about the Alabama teen’s disappearance. The whole ordeal seemed straight out of a Hollywood screenplay. A beautiful, blond, small-town girl celebrating her high school graduation in Aruba had vanished without a trace, leaving unanswered questions in her wake.

The teen’s case became a media sensation, with international law enforcement agencies joining the search. Holloway’s body hasn’t been found, nor her killers brought to justice, but her story has been heard all around the world. The same can’t be said for the hundreds of thousands of others who go missing ever year, especially if they are people of color.

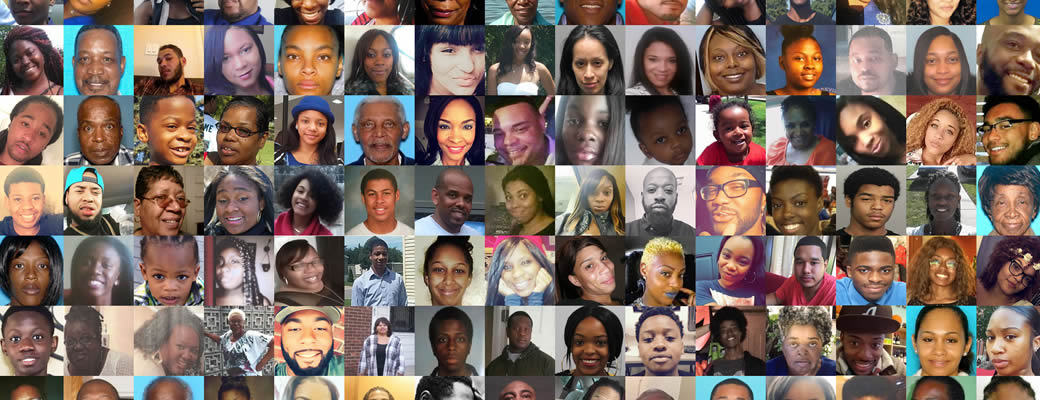

According to the National Crime Information Center, 661,593 people were reported missing in 2012. Forty percent of those, 265,000 individuals, were people of color. Of that number, African Americans comprised 85 percent. Despite the shocking number of minorities who vanish each year, their stories garner less than a fifth of the media coverage of white victims. That has inspired Natalie Wilson and her sister-in-law Derrica Wilson to act.

A young lady named Tamika Houston went missing from Spartanburg, S.C., which is Derrica Wilson’s hometown. “We read about her family and how they struggled to get any type of media coverage,” says Natalie Wilson, who cofounded the Black & Missing Foundation in 2008 to help raise awareness and locate victims of color.

Houston disappeared a few days before Holloway, but her family was unable to get her case on the national media radar. The Wilsons decided to look into why Houston’s family was having such a difficult time spreading the word. What they found has launched a movement to raise awareness around missing people of color and help them receive the media coverage their cases so desperately need.

Derrica Wilson, a former law enforcement official, and Natalie Wilson, a public relations specialist, draw on their professional experiences to help families spread the word about their missing loved ones.

“We decided to do some research and saw that there’s a disparity in coverage,” says Natalie Wilson. “We started the organization because we’re women of action, and we want to help find our missing. We want to protect our families as well as those in our community.”

Over the last few weeks, several media outlets have reported that there are more than 64,000 missing black women in America, but according to Natalie Wilson, that number only tells part of the story.

“We are seeing an increase in not only women but men and children that are going missing,” she says. “They go missing for a number of reasons: human trafficking, domestic violence, wandering away, those victimized through random acts of violence, and mental illness.”

While many of the people are found, Natalie Wilson says a larger segment of the population is missing, but their disappearance isn’t documented. “We hear this all the time from families,” she says, noting that many of the people she’s worked with mistakenly think just talking to law enforcement officers generates a missing person’s report. Other times, law enforcement officials are hesitant to classify people of color as missing.

“The key here is that many times when our children go missing they’re classified as a runaway, and if they’re classified as a runaway they don’t received an Amber Alert or any type of media coverage at all,” she adds. “We tell families that you know your child or family member better than anyone else. If you know your family member didn’t run away, don’t let law enforcement classify them as a runaway, because they will.”

Natalie Wilson points to the Anthony Sowell case as an example of law enforcement officials failing to take the cases of missing people of color seriously. Sowell, a convicted sex offender, was suspected of killing 11 women in Cleveland between 2007 and 2009. Though Sowell was later convicted on all but two counts, his victims’ families claimed police ignored their concerns about their missing loved ones, which allowed Sowell to continue his killing spree. That extreme disregard of victims’ families is a trend that has been replicated across the country.

“Sadly there’s a stereotype about the minority community that there’s criminal activity, and people are becoming desensitized, thinking it’s normal,” says Natalie Wilson. “We need to get out of that mind-set.”

“We will not see all of these individuals returned within our lifetime, but we at least want to try,” she says. They’ve done more than try. To date, the Black & Missing Foundation has helped locate more than 125 missing people or reunite them with their families, but with thousands of others still missing, the job is never-ending. “We have a long way to go,” says Natalie Wilson, “but I believe we’re making an impact, and we’re not going to quit.”

Photo credit: Black and Missing Foundation