When a Black Woman Disappears, Who Is Trying to Find Her?

ZORA

Janelle Harris Dixon

October 12, 2020

The inside of a midsize storage unit in Prince George’s County, Maryland, is stacked, floor to ceiling, with the belongings that tell the story of Unique Harris’ life interrupted. Small, dainty pieces of her jewelry. Framed pictures and family photo albums. Her favorite jacket, clothes, and personal toiletries. They’re bagged and boxed, shielded from dust and potential damage, but it’s a sensory experience for her mother, Valencia, to see, touch, even smell her daughter’s valuables. For a few moments, she holds the nozzle of a half-full bottle of perfume to her nose and inhales the fragrance. Its familiarity almost instantly invokes a wave of sorrow. “It’s Unique’s favorite,” she said, crying silently. “It smells like her.”

It’s been 10 years since Harris has seen the eldest of her three children, 10 years of not hearing her laugh, wrapping her in a hug, or talking to her on the phone. On October 9, 2010, Unique, then 24, disappeared from her southeast Washington, D.C., apartment at The Courts on Harford Street somewhere between 3 a.m. and 8:30 a.m. Her eight-year-old niece and her two sons, just three and five, were sleeping in the living room, her purse with her debit card and ID inside was where she usually kept it and there were no signs of forced entry around the doorway. The only items missing were her cellphone and keys but most troubling was what was left behind — Unique’s eyeglasses. Her mother says she was extremely nearsighted and never went anywhere without them.

“I knew there was a problem when my dad found them on her pillow,” Harris remembered. “They’re a pair of Dolce and Gabbana glasses that my daughter had saved up for months to get. She was so happy when she got them, she called me and told me about them, and sent me a picture of her with them on. So I still have her purse and I still have her glasses.”

Unique’s case is the oldest on the Metropolitan Police Department’s missing persons website, where the people profiled are consistently and almost exclusively Black and Brown, even as residents of color are being systematically pushed out of one of the most rapidly gentrifying cities in the country. Harris says she filed a missing person report within an hour of discovering that Unique was gone. Her case information was entered into NamUs — an abbreviation for the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System — on February 2, 2011, nearly four months after she vanished. Still, in the decade that has elapsed since Unique disappeared, there has been little development and few answers in the investigation. Frustrated by long lapses in activity and communication with detectives, Harris has been her own best advocate to keep Unique’s disappearance from being swallowed by the obscurity of the cold case file room.

“Before the D.C. police department even generated a flyer, me and my family hit the streets with our own flyers, especially in Unique’s neighborhood. Then they put out a noncritical missing persons flyer. That was insufficient for not only my daughter’s case, but anybody’s case. I mean, what the hell is a noncritical missing person?” said Harris.

The determination to elevate a noncritical missing person’s case to critical status depends on the age of the individual (younger than 15 and older than 65), whether they have any mental health or addiction disorders, if they rely on prescription medications like insulin, if there’s any history that they’re a danger to themselves or others, or if they’re in a potentially life-threatening situation, explains Captain Carlos Heraud, head of the Metropolitan Police Department’s homicide branch, where Unique’s case was reassigned in November 2011.

In general, he believes police departments invest an appropriate and equal amount of time and research into finding answers about the disappearances of Black men, women, and children. The hard truth is that not every person gone missing is an emergency, he says.

“Sometimes families feel that just because they’re not given every tidbit of information, their case may be falling by the wayside or it may not be given the attention that they feel it should. But there might be a lot of legwork or investigative efforts the detective may have put in that they’re just not privy to,” said Heraud. “If there’s foul play, we develop a suspect or, in the unfortunate circumstances that it turns into a homicide, we have to maintain the integrity of the investigation somewhat to ensure a successful prosecution, if and when a case ever makes it to that point.”

Research indicates that cases involving African Americans remain open and unresolved four times longer than cases involving White and Hispanic people. So missing Black women, like Unique, are twice victimized: once by the crime that ripped them from their lives in the first place, and again by ineffective law enforcement processes and a media largely indifferent about their disappearances. It’s what journalist Gwen Ifill identified as the “missing White woman syndrome,” an indictment of the press’ coverage of stories that only check the standard boxes for public interest and sympathy (see: Natalee Holloway and Chandra Levy).

That puts a premium on social media as the go-to resource to put the Black community on alert about a case, says Natalie Wilson, co-founder and chief operating officer of the Black and Missing Foundation, a national nonprofit that advocates for missing persons and supports their families.

“Many times when our women go missing, they’re believed to be involved in some type of criminal activity and that’s not true,” she explains, referring to the case of Anthony Sowell who, in 2011, was convicted of murdering 11 women — all of them Black — and hiding their bodies in and around his Cleveland, Ohio, home. “I remember family members contacting us saying, ‘Hey, we reached out to law enforcement and they didn’t take us seriously. They said that our loved one is on drugs and the drugs will wear off, or they’re involved in some type of promiscuous behavior.’ Basically, blowing them off,” Wilson said. “So we have to be vigilant about these cases. We have to take them seriously.”

Last year, more than 205,000 Black Americans were reported missing, according to the National Crime Information Center, and Black women, who make up less than 7% of the U.S. population, comprised nearly 10% of that number. A 2019 report compiled by the Congressional Research Service reveals that African Americans are overrepresented in the number of missing persons cases compared to the population as a whole. The FBI estimates that some 64,000 Black women and girls are currently missing. The urgency to understand what’s happening to so many sisters is obvious when it’s laid out in numbers.

Toni Jacobs sensed something was wrong on September 26, 2016, when her then 21-year-old daughter, Keeshae, hadn’t called or texted by her lunch break. They were close — Keeshae even has a tattoo of her mama’s name on her shoulder — and daily communication has been part of their routine. By the time Jacobs got home from work, nearly 16 hours since she’d last spoken to her child, she was in a full-blown worry. By 1 a.m., she was knocking on the doors of friends’ homes where she thought Keeshae could possibly be. But when Jacobs went to police in Richmond, Virginia, to complete the fearful task of filing a missing person report, she says officers didn’t match her concern.

“The first thing they said was, ‘How do you know she’s missing? She just could just not want to be found.’ I literally had to show the police officer my phone like, this girl texts me every day, all day, and I haven’t heard from her,” Jacobs said. “If that was the case, she could’ve said, ‘Hey Mom, look I’m going to so and so. I’m chilling. I’ll contact you.’ But that’s not what happened. Her last message said, ‘Mom, I’ll see you in the morning.’ And morning came and I ain’t seen my daughter.'” Even following her explanation, Jacobs says Richmond police didn’t start investigating until a week later.

Then in January 2017, just three and a half months after Keeshae vanished, Jacobs’ 25-year-old son, Deavon, was shot to death. Headlines read “Missing woman’s brother murdered at Richmond motel.” Finally, the public was paying attention to Keeshae’s case. It took the killing of her only sibling and her mother’s only son to elevate media interest and investigative action.

“Trust and believe, if she was a White girl, they would’ve been on it within the first 24 hours. When it’s women with children and husbands, they’ll be on the news. I literally had to fight to get Keeshae on the news,” said Jacobs. “People have this misconception when somebody goes missing that they ran away, they had problems at home, they probably was abused. My daughter was not abused. She didn’t run away. She held my hand and hugged me before she walked out my door.”

In December 2018, as one of his last presidential moves of the year, Trump signed the Ashanti Alert Act into federal law. The new nationwide system dispatches notifications about missing people between the ages of 18 and 64 — too old for an Amber Alert, designed to make the public aware of child abductions, and too young for a Silver Alert, which similarly dispenses information about missing seniors. It is the legislative namesake of Ashanti Billie, a young, Black woman and aspiring chef who moved from Maryland to Virginia Beach to study culinary arts. On September 3, 2017, Ashanti was kidnapped on her way to work. Because she was 19, no be-on-the-lookout alerts went out about her abduction. Then 11 days later, her body was discovered near a church in Charlotte. Her parents, Meltony and Brandy Billie, and lawmakers pushed the act to help expedite searches for missing and endangered adults so Ashanti’s senseless death could save another life.

For years, Harris and Jacobs have been a mutual support for each other, part of a sorority of nightmarish circumstances they never wanted to be initiated into, each carrying a daily anguish that is raw and unrelenting, each vigilant in her belief that her child is alive until there is a body to prove her wrong. Unique and Keeshae have lives waiting for them to rejoin. In December, Unique’s oldest son will be 16 years old; her youngest is now 14. She has a nephew she hasn’t met yet, born a few years after she disappeared, and she had just been accepted to an academic program. Keeshae is a hard worker and would be excelling at whatever job she’s doing. Her mother just bought a home and jokes that Keeshae would be there every weekend, centering herself in the tight-knit family she loves and loves her back.

Even when the media is indifferent and law enforcement is underperforming or uncommunicative or both, it just takes one regular, everyday Samaritan to come forward with the information or tip that can help find a missing person or provide closure for their loved ones, says Wilson.

“We ask families to just hold onto hope. Whether it’s the first day or an anniversary, if you have new information about an individual, share it. They are mothers and fathers, they are sisters and brothers and grandparents and cousins and nieces and aunts and uncles. They’re not faceless. They’re important to their community.”

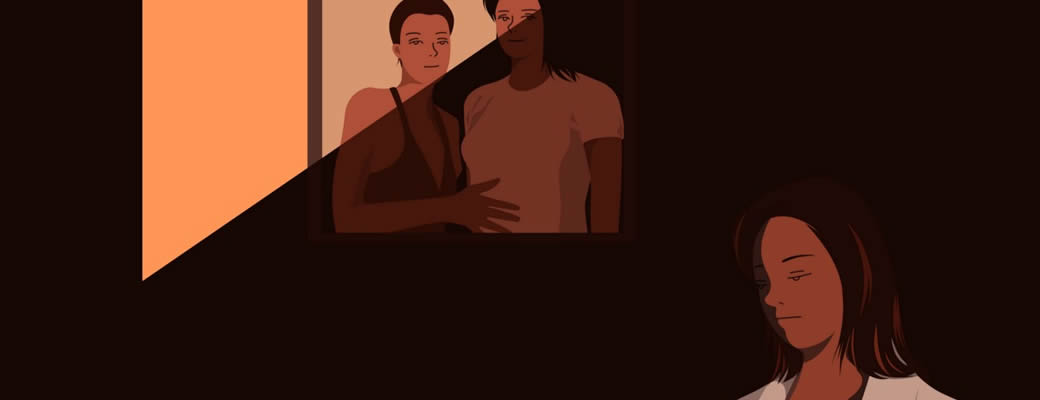

Photo credit: Charlotte Fu