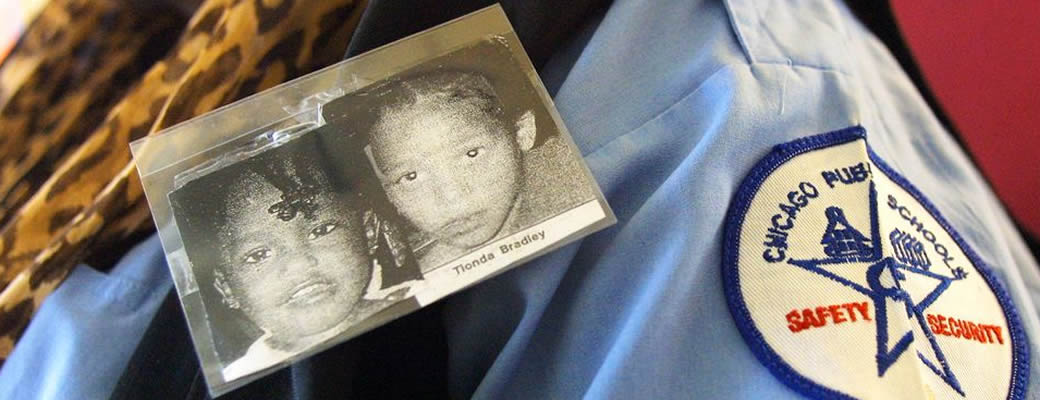

The Bradley Sisters Went Missing 20 Years Ago—And Their Aunt Hasn’t Stopped Searching For Them Since

Oprah Daily

Leigh Kunkel

July 22, 2021

In 2001, a 10- and 3-year-old went missing in Chicago—a case that’s since become complicated by time, trauma, and relations between law enforcement and the Black community.

Just before dawn on July 7, 2001, Shelia Bradley-Smith climbed into her ’97 Dodge Caravan in the parking lot of a housing complex on the south side of Chicago. She did not buckle her seatbelt or ease the car out of park.

She sat. Watching.

The complex comprised two blocks of apartments that bordered the south and east sides of the lot; the west was hemmed in by S Cottage Grove Avenue, intersecting at a diagonal with E 35th Street, which formed the lot’s northern boundary. Across 35th was the low brick facade of the Sixth Grace Presbyterian Church, silent in the crepuscular light. Humidity had been building in the air for hours, spilling over briefly into drizzle just as the day broke and then settling, sticky and thick, over the city. The tip of Shelia’s cigarette shone orange, framed by the metallic blue body of the van.

Every person she saw, she wondered, Was it you?

Was it you who took those little girls?

Shadows shrank, going from an even blanket across the landscape to distinct shapes that stretched across the sidewalk. Shelia waited, patient as a desert predator in the shade of its burrow, although everything inside of her was screaming, knowing her two little great-nieces could be getting farther and farther away.

She watched the first city bus of the day roll through in the new morning sun, watched as the crossing guard arrived around 7 o’clock to escort neighborhood children across the busy intersection, watched the students from a nearby learning center disembark their yellow bus an hour later. She noted the comings and goings of the neighbors and their visitors.

Was it you?

Any one of these people might know who did it. Any one of them might have done it.

In the late morning she retreated to her niece’s apartment for several hours but returned to her vigil at 10 o’clock that night. She sat through the dark hours, smoking and sipping soda.

The second morning, a truck full of men arrived at the complex for a carpet job: old carpet out, new carpet in. Were the rolls large enough to smuggle two young girls out of the building? Probably—Diamond was 3, and Tionda was 10, and both were small. The two of them together weighed just over 100 pounds. But other than proximity, there was no reason to distrust the men and, having completed their work, they left without ever knowing that they were, briefly, in the mind of a childless aunt peering through the window in her van, suspected kidnappers.

For the better part of a desperate summer week 20 years ago, Shelia sat in that parking lot, hoping to see something that would give her a clue as to who had taken her great-nieces. But there were no meaningful leads that week, nor, really, in the more than one thousand weeks since. It’s as if time stopped when she climbed into the van on that humid July morning two decades ago.

In many ways, she has never left.

Establishing even the most basic facts of the case of the missing Bradley sisters is difficult, complicated as they are by time, trauma, and the complexity of relations between law enforcement and the Black community. Nearly every reported detail of the girls’ disappearance has, at one point or another, been contradicted by someone. Making the pieces fit perfectly is impossible. There is always a jagged corner sticking out someplace.

Reporting on Diamond and Tionda’s disappearance is equally complex. Several sources, at the urging of a private investigator who has been working on the case since 2001, would not allow their interviews for this story to be recorded, and the investigator was also on the calls.

Ed Carroll, a now-retired cold-case detective with the Chicago Police Department, believes he was brought on to the investigation in 2009, after years of little progress, because no one else wanted it after Marie Biggane, another cold-case detective, left the team, and another detective became terminally ill. It was that big of a mess, he says. So much had been done incorrectly in the initial investigation that they had to start from scratch, reinvestigating every lead from the beginning. In all the years that he worked cases, Carroll says, “this is the only one where I couldn’t rule anyone in or out.” Much of the timeline that exists today is due to Biggane’s work in organizing the sprawling case files and Carroll’s diligence and commitment, even after his retirement, to pressing on.

The family, too, presses on. It’s a strange kind of torture: Each year, you know that the odds get smaller, and smaller, and smaller. And yet each year, your singular hope—this might be the year—persists.

So you hope and you hope and you hope.

What else can you do?

Around 4:30 a.m. on the morning of July 6, 2001, a man named Tom arrived at the apartment where the woman he was seeing on and off, Tracey Bradley, 32, lived with her four daughters: Rita, 12; Tionda, 10; Victoria, 9; and Diamond, 3. [Note: Tom’s name has been changed.] Roughly two hours after he arrived, Tom drove Tracey to her job at the nearby Robert Taylor Homes, another apartment complex, where she helped prepare breakfast and lunch for residents.

Rita and Victoria were at Tracey’s mom’s house, where they had spent the night. Diamond and Tionda were left home, in Tracey’s apartment, with the same strict instructions their mother always gave them: Don’t go anywhere or open the door to anyone.

Tracey called home three times between 8 and 9 a.m. Tionda did not answer any of the calls, which was unusual. Phone records also indicate that several calls from other numbers to Tracey’s apartment went unanswered over the course of the morning, and there were two hang-ups.

At roughly 11:30 a.m., Tracey returned home from work. Usually she would find Diamond and Tionda spread out across the cream-colored couch, watching a show or playing a game. But that day, the living room was heavy with silence. She ran to the back of the apartment, calling out their names, but there was no one there. Fear rose in her throat with every empty room she found. When Tracey returned to the living room, she found a note in Tionda’s handwriting on a lounge chair. It said that the girls were planning to go to a store and then a nearby school playground.

The note is the first of several perplexing clues in the case. Because it is in the sealed possession of the FBI, many people involved in the case have never even seen it, nor is there a public record of its wording. Rita says today that it was Tionda’s handwriting, but “we never in our lives wrote a letter for our mom” and the girls all knew not to leave while she was at work. Many years later, some of Tionda’s classmates claimed to have seen the girls at the playground that day, but after so much time has passed, it’s impossible to corroborate or know how accurate the information is.

Shelia, who is Tracey’s aunt, is also suspicious of the note. “The way Tionda spoke, her grammar, didn’t line up with the grammar in the note,” she says. “And another thing, she wouldn’t have spelled certain words that way—they wouldn’t have been spelled correctly.” While it was determined by the FBI that Tionda did write the note herself, Shelia says, “the question is, was she persuaded to write under false pretenses?”

Tracey made a flurry of calls to neighbors and family members. Her sister Faith picked Victoria and Rita up from their grandmother’s house and soon the entire extended family was fanning out to search for Diamond and Tionda. According to police reports, Tom, rather than help with the canvass, made plans to meet up with another girlfriend.

They searched the nearby Ida B. Wells housing complex, where the girls had friends they might have gone to visit. They scoured the 31st Street Beach, where they often spent hot summer days cooling off in the waters of Lake Michigan. They traversed the bridge over the busy expressway, hoping to intercept the girls as they wandered. But no one had seen Diamond or Tionda, nor was there any indication that they’d visited any of their favorite spots that day.

Just before 7 p.m., Tracey called the police to report her daughters missing. At this point, they had been gone for at least seven and a half hours.

The Chicago police responded immediately, which is—statistically and anecdotally—unusual for a case involving missing Black children. The initial search for the girls involved three beat cars, two supervisors and two canine units which combed the neighborhood, including dumpsters, yards, vacant lots, businesses and the lakefront. Eventually, the search would expand to become the largest missing-persons search in Chicago’s history at the time, including involvement by the FBI and a tip line that brought in 824 tips, none of which went anywhere.

To some observers, Tracey appeared uninterested in following up on leads in the early days of the disappearance. At one point, a surveillance video from a nearby store surfaced that might have shown Diamond and Tionda, but Tracey initially declined to view it to confirm. (The video was ultimately determined to be unrelated.) When police would go to her house with additional questions or to bring her information, she sometimes refused to interact with them.

Even now, Tracey is difficult to contact. I was only able to speak with her on a conference call mediated by Pablo Foster, the family’s private investigator, who requested that I not tape our conversation.

But many of the criticisms others have leveled against her become less clear-cut when you talk to her. The decision to delay calling the police, for example. She says that most parents will never have to face the terrifying, confusing ordeal that she was experiencing, and couldn’t imagine what it’s like. “I just wanted to search on my own. I wasn’t even thinking about the police,” she says. “Any parent would do the same that I did.”

When she speaks about the case to me, her words are alternately hesitant and forceful. Her comfort with discussing something so intimate and painful seems to wax and wane from moment to moment. It is a quality that does not lend itself to simple narratives of familial pain and love. People’s rush to judge the quality of her grieving exacerbates the problem, and the cycle continues.

Adding another layer of complication to the situation was the fact that, like many Black families, the extended Bradley family had traumatizing past experiences with law enforcement. When Faith asked Tracey earlier in the day if she’d called the police yet, Faith recalls, Tracey told her that she was afraid of being reported to the Department of Children and Family Services.

“There’s a sense of distrust between the minority community and law enforcement,” says Natalie Wilson, co-founder and chief operations officer of the Black and Missing Foundation, a nonprofit that works to raise awareness of missing people of color. “If you look at what’s going on now in our communities, it didn’t just start. That relationship has been like that with law enforcement due to racial injustices for many, many years.”

The morning after the disappearance—when Shelia was on her parking lot vigil—Tracey’s sister Faith says she decided to check the voicemail on Tracey’s cell phone, which Tracey had not done. (Faith had set up the family plan and knew all the PINs.)

There was a message from Tionda.

“She said, ‘Mom, mom, answer the phone! Tom is at the door with the cake,’” says Faith. The whole family listened to the message, she says, as did the FBI agents who were at the house.

Tom is also the name of the Bradleys’ neighbor and family friend (his name, like the other Tom’s, has been changed), who was helping search for Diamond and Tionda. However, that Tom actually went by a distinctive nickname, which Tionda would have used. The consensus was that Tionda was likely referring to her mother’s boyfriend.

After that day, the voicemail seems to have vanished. Faith thinks it may have been accidentally deleted. Tracey says she never heard it. Shelia says it “disappeared” but won’t give further detail. Foster, the private investigator, was cagey but intimated to me that the FBI has it. The only thing known for certain is that the Chicago Police Department does not have it in their evidence locker. Ed Carroll, the retired cold-case detective, says he pleaded with anyone who might have the tape to share it with him: “I told them I’d go anywhere in the United States to find it, but no one could ever tell me where it was.” The tape could open up whole new avenues of investigation, he says.

Another twist: There’s no record of a call from Tracey’s home to her cell phone that day.

When terrorists attacked the World Trade Center and the Pentagon just two months after the Bradley’s disappearance, media attention to the girls’ disappearance dried up, and so did most of the leads. As the weeks went by, Tracey entered a zone in which it was painful even to speak. She couldn’t do anything but sleep and pray.

But the police were still working the case, and their search started to zero in on one man.

Tracey and Tom had always had a complicated relationship. It was made even more so when she became pregnant with Diamond. Tom denied paternity; however, not long before the girls’ disappearance, Tracey had demanded that Tom take a paternity test. The results came in just three weeks after Diamond vanished. He was her father.

In the days leading up to July 6, Tom did something out of character: He planned a camping trip for Tracey, Diamond, and Tionda, even though the group had never been camping together before. “Planned” might even be too strong a word: Tom hadn’t made reservations, despite it being Fourth of July weekend, nor had he bought any food for the trip, and he had borrowed only minimal equipment, according to police records.

The trip would have been unusual not only because of its novelty, but because Victoria’s eighth birthday was the next day and she was not invited. Tom had never played a parental role in the Bradley girls’ lives; at the time, he still denied he was Diamond’s father. In fact, the girls rarely interacted with him other than an occasional car ride.

“Why would he take just two of the kids camping when we’d never done anything together with him?” says Rita, who was also not invited. “He probably had something up his sleeve. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to see.” Tom has never been charged with anything relating to the girls’ disappearance.

On July 7, the day after the disappearance, receipts indicate that Tom bought a package of 42-gallon contractor bags, gardening gloves, and a pair of neoprene protective gloves. When police searched his home several days later, there were five bags missing from the roll and the gardening gloves were not found. A neighbor said they had seen Tom burning something in a 55-gallon drum and several others noted they had seen him loading it into the trunk of his car, returning approximately 45 minutes later. Tom denied that these events took place, but FBI reports note evidence of charring on the rafters of his garage, as well as striations in the trunk that matched the size and shape of a trash barrel.

If what was in the barrel was related to Diamond and Tionda’s disappearance, Carroll says, it was likely only their clothing, because neighbors would not have been able to forget the distinctive smell of a burning body.

Also found in Tom’s trunk was a blanket containing several hairs later determined to belong to Tionda. Tom claimed that he had taken Tracey and her daughters to a drive-in movie and made Tionda and Diamond hide in the trunk so that he would not have to pay for their tickets, something that Rita vehemently denies ever happened. The logistics are also questionable: Only one drive-in theater was operational in Chicagoland at the time, nearly an hour away.

Tom was a prolific cell phone user, even in 2001. Beginning at 4:30 a.m. on July 6, he made at least 40 phone calls over a period of 24 hours. There are two stretches during which he called no one: from 7 a.m. to 9 a.m., immediately after he’d dropped Tracey off at work and while the girls are presumed to have been alone in the apartment; and from 5 p.m. to 6:30 p.m. His calls preceding this second window pinged off of cell towers on the far south side of the city, near multiple forest preserves and the Little Calumet River. At one point, Tracey reportedly told her cousin that “if Tom did do something to those kids, they may be where he used to take me walking in the forest.”

As he worked on the case in the early 2010s, Carroll made sure to always loop in the office of Anita Alvarez, then the State’s Attorney for Cook County, to ensure that they were aware of any updates or new information; he hoped that the office might decide to convene a grand jury. “I always thought it could shake something loose from the trees,” he says. “People make mistakes when they’re under pressure, even years after the fact. Alvarez’s office never moved forward, though.”

The goal of a grand jury is to establish whether to bring criminal charges or an indictment against someone; it does not have the power to convict anyone. But its benefits can be particularly important in a situation like the Bradleys’, with so many complexities and moving pieces. Grand juries can subpoena witnesses who might otherwise refuse to speak to law enforcement, and because their testimony is sealed, also offer them a degree of protection that could encourage them to be more forthcoming. In the Bradleys’ case, convening a grand jury could not only help determine if and when the case is sufficient to move forward to criminal court, but would also have the advantage of getting witnesses’ testimony on the record for any future investigations or trials.

However, while many districts use grand juries as fact-finding missions regardless of the imminence of a criminal trial, Carroll’s experience with Cook County is that the court system only convenes them when they’re also ready to bring criminal charges. One reason Cook County could be reticent to call these witnesses, he believes, is that if their stories were to change between the grand jury and a potential criminal trial, it would be easier for defense attorneys to discredit them. But, as one of the few people who has gained the family’s trust, listened to their statements and feels confident in their testimony, he thinks it is a risk worth taking.

Chicago district attorney Kim Foxx has the power to reconsider the value of a grand jury in this case, but her office seems to be following in the path of her predecessor’s. In a statement to Oprah Daily, her office said, “The Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office has not been asked to review criminal charges related to the disappearance of Diamond and Tionda Bradley. We are open to reviewing any information that is brought to us by law enforcement, who is handling the investigation of this case.”

The FBI, for its part, remains interested in the case, but identified the Chicago Police Department as the “lead investigative agency.” “The FBI is still actively providing investigative assistance to the Chicago Police Department with respect to the disappearance of Diamond and Tionda Bradley,” says Special Agent Siobhan Johnson of the FBI’s Chicago office. “We continue to seek the public’s assistance in identifying tips and offer a $10,000 reward for Diamond and Tionda.”

As Carroll points out, criminal charges are not required to call a grand jury, and in a case like this, where the single thing that might bring it back to life is new information, it could be the best—or only—way forward.

Several tantalizing leads have surfaced over the years. The first, in 2008, was a MySpace photo nearly identical to law enforcement’s age-progressed pictures of Tionda. Shelia brought in a well-known forensic artist who believed that the girls were one and the same. Eventually, however, the identity of the girl in the photo was determined, and it was not Tionda. The girl keeps in touch with Shelia, though, hoping for positive news.

In 2019, after Shelia posted a plea for the girls to come home on Facebook, a woman in Texas responded, “We’re trying.” When Shelia began to message her asking for specifics, though, the woman’s story soon became suspect. “She became highly aggravated and disappointed at the same time,” Shelia said at the time. “She said, ‘Auntie, of all the people, you should know this is me.’” It was a hoax.

Shelia has taken on the search with extraordinary devotion.

On March 20, 2015, she was driving a long westward stretch through Wisconsin after helping her daughter move. An emergency alert flashed on her phone:

Ten-year-old Barway Collins was missing from Crystal, Minnesota, where Shelia still lives.

Not in my damn backyard, she said to herself as she urged the truck on a little faster toward home. Not in my damn backyard.

The next morning, moved by the same drive that made her sit in her van night after night all those years ago, Sheila made flyers for posting and stood with a bullhorn outside the apartment building where Barway lived, exhorting his neighbors to join the search. For three straight Saturdays, she organized hundreds of volunteers to canvass the surrounding area. When it was revealed that Barway’s father’s cell phone had pinged near the Mississippi River the morning of the boy’s disappearance and then again 20 minutes after he was last seen alive, Shelia redirected the search to its shoreline and the nearby railroad tracks. The police had already traversed part of the area, but Shelia had a gut feeling the boy was there.

It was sunny but the temperature hovered just above freezing in the early hours of April 11. Shelia leaned out the window, cigarette smoke drifting up toward the sky. The boy was still missing. “Barway,” she said to whoever might be listening, “Barway, you gotta help me today.” As she prepared to organize the day’s canvass, she brought blue and white balloons to release: blue for Barway, white for her prayers.

The various search factions set off; Shelia herself was visiting a nearby building that housed sex offenders, hoping someone would have information to share. When she returned to her van to collect more flyers, her phone rang.

“Is this Miss Smith?” It was a young boy. For a moment, in Shelia’s heart, it was Barway, safe and alive. Your mind can play tricks on you that way, when you’re looking so hard, for so long, for one thing. The boy continued: “I’m with the searchers and we’re by the Mississippi.” A troop of Boy Scouts had joined the search, and one of them was calling to report seeing “lots of stuff,” like fishing poles and garbage.

Shelia thanked him and urged him to continue looking.

He called back.

“Miss Smith, either this is a big old tree or it might be a body.”

Barway’s body was still partially bound with duct tape; it wrapped around his abdomen, though his arms had broken free and floated stiffly away from his torso like branches. The average water temperature hovers around 40 degrees that time of year, but decomposition was well underway.

Shelia walked the riverbank, near where, she would later learn, the boy’s father had left his body after striking him. She fell to her knees among the trees and bushes, and again and again asked, through her tears, “How could you let me find someone else’s but not my own?”

The shape of a loved one’s absence changes from person to person. Tracey sees the girls in motion: The long, graceful limbs of ballerinas remind her of the love of dance she and Tionda shared. Looking at the couch, she can see Diamond leaping from cushion to cushion. For Rita, the absence is shaped like a bowl of rainbow-streaked milk, leftover from Millville Fruity Rice cereal—one hot summer day, Tionda had snatched the last milk carton at lunch and Rita thought she would have to go without. Instead, when Tionda finished her cereal, she saved the colorful milk for her older sister. The memory still makes Rita cry. She says Tionda was different from most other kids her age. Generous and kind.

These moments, bittersweet in retrospect, now compete with the other legacy that Diamond and Tionda have left behind, which is one of fear. It has made both childhood and motherhood fraught for the Bradleys, affecting three generations of women and their children. When she was young, Rita worried that whoever took Diamond and Tionda might return to kidnap her and their other sister, Victoria. Now a mother herself, it is fear for her own children—her oldest is 12, the same age she was when her sisters vanished. “It makes me stricter,” Rita says. “I don’t let them go to people’s houses that aren’t family members.”

Tracey, too, has become more protective, and more fearful, even as her children become parents themselves. And she has had to navigate those changes while under the critical eye of the public.

“I’m not a bad mom,” she says, her voice rising with passion. “I know who Tracey Bradley is. I know who I am, and I don’t let that reflect on me or my kids or my life because I’m still a good mom.”

Even without their physical presence, she is still a mother to Diamond and Tionda. “You are always a mother,” she says.

For Shelia, the loss has changed her in ways both personal and professional. “I’ve never taken a job since they were kidnapped that couldn’t provide me with some kind of information or a way to keep an eye on everybody,” she says. “I don’t take jobs unless I’m able to obtain information.” She’s been a public aid caseworker and worked in the pediatric ward of a hospital, hoping that one day the girls, or someone with information about them, might come through. It is, she says, part of being a “desperate auntie.”

“You have people saying, ‘Well, the auntie does more than the mom!’” Shelia says, disbelief in her voice. “And I’m saying, what’s the difference? We’re family.”

Every year as the sixth of July approaches, the preparations begin anew: stopping at the copy shop to pick up fresh banners and color fliers featuring images of the girls and pleas for their return; ordering T-shirts from the custom shop, pressed with Diamond and Tionda’s faces outlined by a heart; picking up balloons, sometimes purple and white, sometimes pink and yellow, to release against the blue summer sky.

There are variations. One year, it was floating lanterns instead of balloons. Another time, doves flew into the afternoon air. Last year, the family had COVID-19 face masks printed along with the shirts.

Shelia and several other members of the family usually meet early in the afternoon near the new 35th Street Bridge, which has replaced the one they crossed so many years ago as they searched for their girls. Though the main event has moved to a park farther south, the Bradleys do not want their old neighborhood to forget their pain or their hope: The girls are still gone, but someone could still come forward.

Later, crowds begin to arrive for the vigil at the park on 47th. Motorcycle brigades and lifelong friends, family members and Facebook followers all converge on one of the wide green fields under the July sun. There are hymns and hosannas, Tracey sometimes lifting her hand as she sings, as though it might help a mother’s prayers reach a higher plane. Then the release of balloons and with them the stasis of unresolved grief, making way for the possibility of something fresh: a tip, a clue, a confession.

Maybe this will be the year.

Grills are fired, coolers set out. Children too young to know Diamond and Tionda through anything but family lore scamper across the playground while their parents eat and laugh. Often there is a cake for Victoria, whose birthday is the next day.

Afternoon passes into evening and sometimes a beat cop arrives to remind the family that the park has closed. They pack up the banners and coolers and children and reconvene at someone’s apartment, where they drink a bit to ease the pain. The nature of their grief may have evolved over the years, but it has never lessened. “We don’t get past July 6 of 2001,” Shelia says. “It’s the same feeling, but it hurts a little more because then we realize that it has been almost 20 years. We relive that day every day. It doesn’t change.”

What began as a solitary, hour-by-hour vigil, cigarettes and soda in a silent parking lot at dawn, is now measured in years: the year Tracey moved away from 35th and Cottage Grove, unable to bear the memories; the year a Boy Scout found Barway but nobody found Diamond or Tionda; the year Rita became a mother and couldn’t share the joy with two of her sisters. Marked by different milestones, marred by the same desiderium. Twenty years sitting in that van, peering out at the world, watching everyone who passes by and whispering the same question over and over:

Was it you?

Was it you?

Was it you?

Photo credit: Getty Images